How I became an apprentice at the Atelier Lacourière, the Parisian studio where Picasso, Chagall, Matisse, Calder, Giacometti, Henry Moore, Miró, and other great artists worked

I bounded up the stairs of the Métro and surfaced at Place Pigalle. It was 7 a.m. and I had an hour to kill before my appointment with Jacques Frélaut, the master printer and director of the Atelier Lacourière-Frélaut in Montmartre.

I went into a café and ordered a café au lait and a croissant. The day before, I had moved into maid's quarters under the roof of a bourgeois building on Avenue de la Grande Armée, a few streets away from the Arc de Triomphe. My friend Nils Furto, a Swedish artist whom I had met in Nice, had arranged to find me this little room in Paris and had set up a meeting with Jacques Frélaut.

While savoring my croissant, I was thinking I knew almost nothing about fine art printmaking. The previous year I had finished my philosophy degree at the University of Nice, and my only exposure to printmaking was through an artist friend who engraved fine silverware, and another who was doing carborundum prints—and Nils, who had taught me some basic skills in his own studio.

I had decided to go to Paris to pursue a childhood dream… to have a career as an artist. But I needed a job to cover my living expenses. The weather that morning was clear and cool. I slowly climbed the stairs on Foyater Street. The Sacre Coeur was there, right in front of me, and almost at the last landing of the stairs of Montmartre, I stopped at Number 11. No name on the door.

I entered. A little man was lining up huge square stones on a stack of grey cardboard. "Hello!" I said. “I have an appointment with Jacques Frélaut.”

“Bonjour," he responded. "Wait a minute, I will go and find him.” On the right, hundreds of sheets of grey cardboard were hanging from the ceiling. On the left, a hallway with flat-file cabinets flanking both sides. At the end, a room with a bright window. In front of me, a small staircase that descended into obscurity. A strong odor of ink, linseed oil, and wet paper permeated the air.

After a few minutes, Jacques Frélaut came up the stairs with smiling eyes and a grin on his lips, “Pascal?”

“Oui, bonjour Monsieur.”

“So it’s you who wants to work here?”

“Yes.”

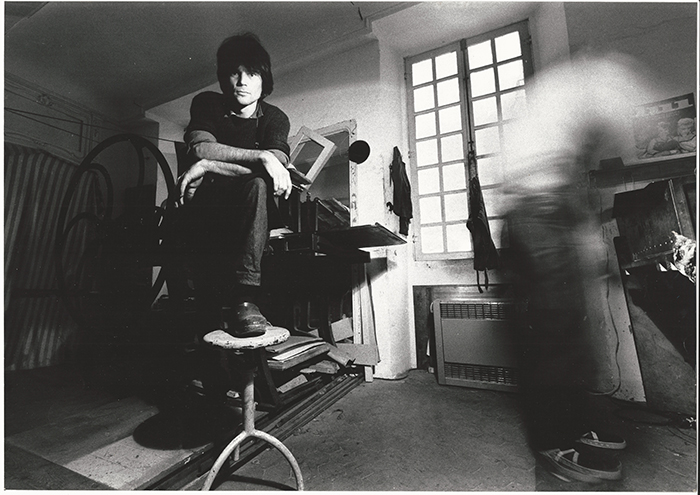

He shook my hand and invited me to follow him down the stairs that opened into an immense room. Bright, tall windows opened over the rooftops of Paris. A dozen old cast-iron presses, tables, huge wooden paper presses, felt hanging from the ceiling, and a buzzing ambient noise from all the work and activity going on around me.

Jacques introduced me to the other printers, then he took a broom and handed it to me. “Your first tool,” he stated. The studio went silent; one of the printers lit a cigarette, another poured a glass of wine, and a third began cleaning his eyeglasses. Everyone was staring at me.

Internally, I noted that if I took the broom, l was effectively accepting the opportunity to become an apprentice, tying myself to a long tradition that dated back to Medieval times, and that this agreement would be a stronger bond than signing any contract.

I took the broom from Jacques. Everyone went back to work without a word, smiles on their faces. My life had begun a new direction.

After several weeks, the broom, mop, and bucket of sudsy water, the oil can, grease gun to maintain the presses, the rag to polish the presses’ brass ornaments—all had become my old friends. For a long time I believed that that gesture of giving the broom was a traditional rite of passage, the entry into the guild and craft at printmaking.

A few months later, one of the master printers told me that when I first arrived at the studio the janitor had been absent for several days. When I met Jacques Frélaut, he had simply needed a replacement and just seized the moment in thrusting the broom at me. So much for the romantic meaning I had ascribed to that first day. Still, the experience was the one detour that altered the course of my travels in life.

My duties at the studio became increasingly more involved. I worked with each printmaker in succession, and as a personal assistant with Jacques. Jacques and the master printers had thirty, forty, fifty years of experience—centuries of accumulated knowledge that was being passed down to me.

Sometimes Chagall, Miró, or another well-known artist would come to work at the studio. I was assisting them and aiding the printer assigned to the project in pulling the test prints up to the bon à tirer. Sometimes they took me to lunch at Chez Barbe, a little restaurant in Montmartre, and we had conversations on art, wine, cooking, life, and again, art.

Following my years at Lacourière, I opened my own printmaking studio in Nice, where I worked with known artists from all over the world. While I had not realized my dream to become one of them, I had found another way of expressing my creativity.

As Jacques Frélaut used to say—paraphrasing Socrates—a master printer is like a midwife, helping artists give birth to the genius that they carry within them.